A Visit to the Met’s Exhibit on Early American Photography

During a recent layover in New York City, I made time to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art to experience The New Art: American Photography, 1839 to 1910. As someone who works with the wet plate collodion process, I was especially drawn to the daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes on display. These are all direct positives. Each plate holds a one-of-a-kind image created inside the camera at the moment of exposure. Seeing them in person reminded me why I fell in love with this process. If you're unfamiliar with tintypes, you can read more about how the process works in my introduction to what tintype photography is.

The exhibit includes more than 250 photographs from the William L. Schaeffer Collection, many of which are being shown to the public for the first time. I found myself particularly drawn to the photographs of American towns and businesses. These were not made in studios but on location. They show the architecture, signage, and layout of streets in a way that feels familiar to my own ongoing project documenting historical buildings in Franklin, Tennessee.

The showing follows a loose chronological structure. The photographs are grouped by process, starting with daguerreotypes and progressing through ambrotypes, tintypes, albumen prints, and gelatin silver prints. This approach gives the viewer a sense of how photography evolved over time while keeping the focus on visual form and content rather than strict historical sequencing. Repetition, posture, clothing, and gaze all begin to stand out. It is less about storytelling and more about observation.

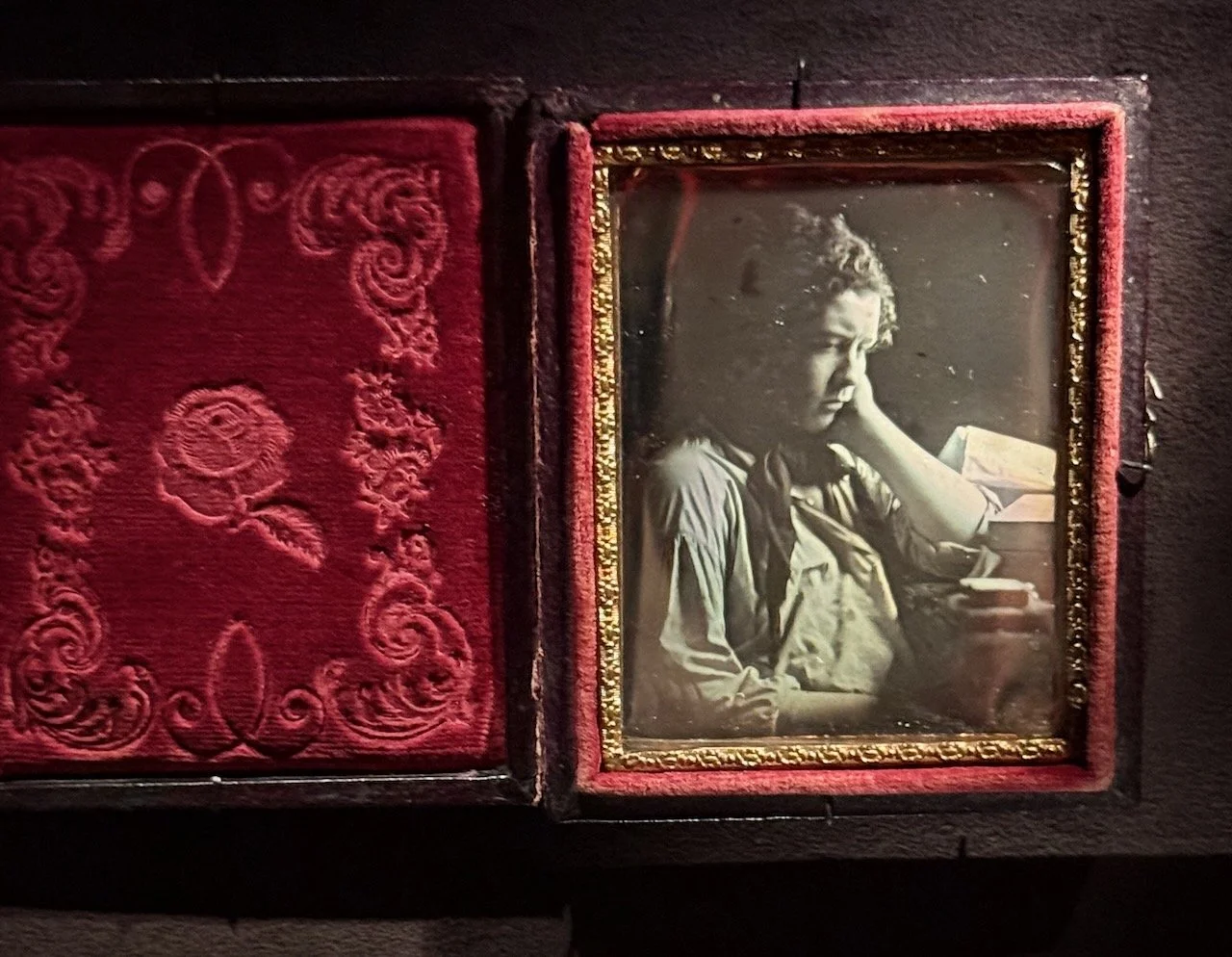

Among the most powerful moments for me were those spent with the early direct positives. Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes all share the quality of being unique physical records. These objects were in the camera with the sitter. When we look at them today, we are not just seeing a picture. We are encountering the very surface that held the reflected light of that person in that moment. It creates a strange intimacy. You feel their presence across time.

Through the galleries, there is also a selection of nineteenth-century cameras placed thoughtfully within the surrounding galleries. Each camera is positioned near the type of photographs it would have produced. A daguerreotype camera sits among a display of daguerreotypes, creating a powerful connection between the object and the images it helped create. A stereo camera is also on view, accompanied by stereo photo viewers that allow visitors to experience the three-dimensional quality of the images. Seeing these tools in the context of the photographs adds depth to the exhibit and offers a tangible sense of the craft behind early American photography.

The exhibit runs through July 20, 2025. If you are interested in early American photography, alternative processes, or simply want to stand face to face with the past, I highly recommend seeing it. These photographs do more than preserve history. They invite us to witness presence. They remind us that photography has always been more than a record. It has been a reflection.

To see how these historic processes live on today, you can explore my Tintype Journal, where I share modern tintypes and behind-the-scenes insights from my studio.